Written by Jessie Saeli, edited by Nicole R. Smith and Rachel J. Bacon

We can’t predict the future, but we want to get closer

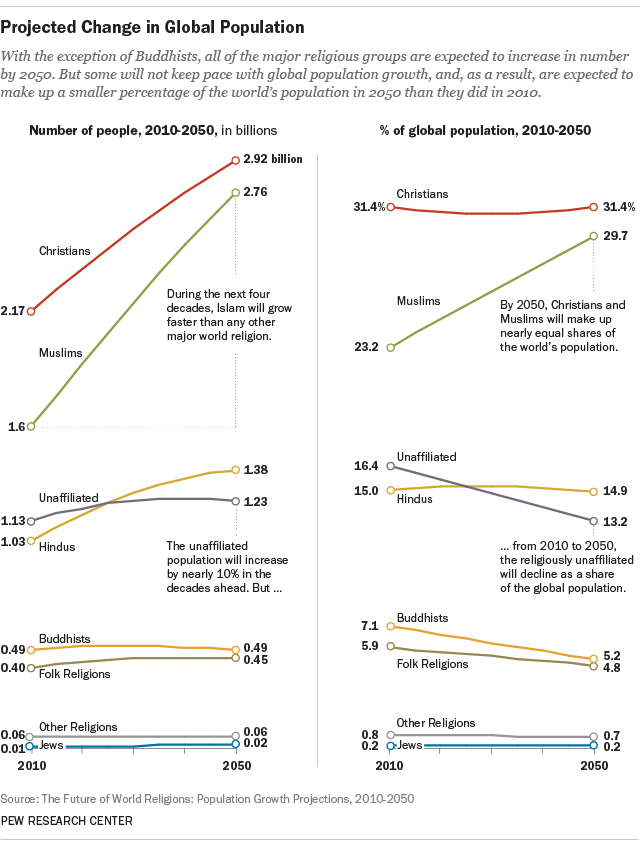

The year is 2050. Although millions of Europeans and North Americans have abandoned Christianity and become nonreligious, the share of nonreligious people worldwide has decreased in comparison to increases in Christian, Muslim, and Hindu populations. Worldwide, the percentage of Christians and Muslims is nearly equal and it looks like Islam will overcome Christianity as the most populous religion by 2070. Regarding the Christians, four out of every ten live in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Ok, sure. What makes you think you can predict the future? Well, we can’t. We’re not even close. But we want to get closer.

How do demographic projections work?

This picture of religion in 2050 was taken from Pew Research Center’s project “The Future of World Religions.” Pew produces demographic projections of religious change based on fertility, religious switching, migration, and mortality.

The term “religious change” might lead you to think of people who convert to or leave a religion, especially in Europe or North America, where more Christians are becoming nonreligious.

However, fertility influences religious composition and change over time as much as, if not more than, religious switching.

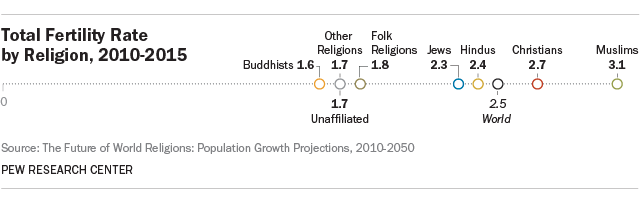

Fertility describes the number of children that the average woman is expected to have. Replacement level fertility is 2.1 children per woman, and as of 2020 the total fertility rate worldwide is 2.4. However, this number varies between religious groups, as shown in this graphic from Pew:

As you can see, Christians have a slightly above average fertility and Muslims are even higher. On the other end of the spectrum, nonreligious people have the lowest average fertility, second only to Buddhists.

Even without any switching between, to, or away from religion, the population of religious groups would change drastically because of differing fertility rates.

Religious switching describes when someone changes their (non)religious identity, such as switching between two religions or between being religious and being non-religious. These numbers vary by religion and country. For example, many people are leaving religion to become nonreligious in the West, but in countries like China, people are increasingly turning from non-religion to religion.

Measuring religious identity and change is a complicated task.

Civic policy and demographic projections

Many nations critically require forecasts of the number of people of various religions for effective civic planning. Collective behaviors such as likely family size, economic security, and migration patterns are strongly correlated with religion. These collective behaviors inform policy and civic planning.

Where and when do we need to build new schools or shut down old ones? How many hospital beds do we need to meet demand? What kinds of social conflicts need to be managed in the short and long term?

Demographic projections of religion inform the decisions of policy-makers for these kinds of questions, which in turn impact the lives of people every day.

The three major problems with traditional demographic projections

(1) Lack of reliable data

Traditional demographic projections rely on the census or survey data to make their predictions. This means that data is often limited by whatever questions about religion are available in the data source, and for which years. Many countries lack consistent data about religion.

In some countries, like the US, the government is discouraged from collecting information about the population’s religion. In other places, collecting data on religion has simply not been a priority.

Non-government groups may conduct surveys that ask about religion, but the questions each survey asks can vary widely and the respondents might not accurately represent the entire population. This consequently limits the accuracy of traditional demographic projections.

(2) Narrow definitions of “religion”

Traditional demographic projections focus on how many people identify with a particular religious group: the answer to questions like “What is your religion?” on a survey.

But religion isn’t just a box you check on a survey; it is multidimensional, including many different practices and beliefs. On its own, religious identity only reveals a small part of the religious landscape.

For example, In Norway, a majority of the population identify as Lutheran, which is the state church. However, less than half of Norwegians believe in God and very few attend religious services regularly. Focusing on identity suggests extremely high religiosity in Norway, but the on-the-ground story is very different.

(3) Inability to account for nuance in the drivers of religious change

Finally, these traditional demographic projections rely on making general assumptions about how fertility, switching, migration, and mortality rates will operate among swaths of the population. This allows demographers to simplify their calculations to fundamental factors of population change among specific (non)religious groups.

However, in doing so, these projections deal with monolithic religious groups without accounting for the nuance of individual behaviors and decisions that drive religious change. They must make very general assumptions that apply to everyone in a group, such as all children have the same religion as their mother or the rate of switching from Christianity to no religion stays the same over time. This greatly simplifies the process of religious transmission from parents and of secularization.

Lack of sufficient data, narrow definitions of “religion,” and the inability to account for nuance in the processes of religious change limit the accuracy of traditional demographic projections, which in turn makes effective civic planning more difficult.

An innovative approach to predicting religious change

We know the limitations of traditional population projections, but what can we do about it?

The Modeling Religious Change project (MRC) is a collaborative project bringing together experts in demography, the scientific study of religion, and computational methods to address these challenges. Our goal is to solve the three problems above (and more) by creating theory-based simulations of religious and non-religious identity and change in the USA, Norway, and India — and, time permitting, Nigeria, Argentina, New Zealand, and China.

We combine traditional social-science methodologies with computer modeling and simulation to predict religious change in the real world. The idea is to create artificial societies with cognitively plausible and behaviorally believable AI agents and then measure the change in religiosity over time in those artificial societies.

How can we solve these problems?

So, how does our cutting-edge, radically interdisciplinary approach improve demographic projections? Well, let’s go through each problem one at a time.

(1) Synthesizing data

The only way to solve the problem of insufficient data is to carefully combine data from different sources — without distorting them — in order to provide the big-picture, decades-long, and country-wide overview necessary for demographic projections.

This takes incredible amounts of time and careful, detail-oriented work. Currently, MRC is working on creating a database of survey data on religiosity in the US dating back to the early 1900s. Using questions about the religiosity of parents from the General Social Survey and other surveys, we are able to extend our picture of religion in the US further into the past.

This bigger picture allows us to identify long-term and short-term trends more accurately and provides us with a larger pool of data to test our models and simulations against.

We are also tailoring our approach to each country. In India, survey data is extremely limited. We are supplementing existing surveys with religious data from an ethnographic collection called the “People of India”. Integrating archived qualitative data and newer survey data poses its own challenge, but we are confident that doing so will give a more accurate picture of the religious landscape.

(2) Dimensions of religiosity

Religious self-identification needs to be supplemented with information on what people actually do and believe. Remember the case in Norway: labeling someone as “Lutheran” doesn’t mean that they hold Lutheran beliefs or participate in Lutheran practices. We are compiling data on multiple “dimensions of religiosity” in order to account for and compare different factors related to religion beyond self-identification alone. Stay tuned for an article in March where we will describe our dimensions of religiosity in detail.

Using multiple dimensions of religiosity is critical to a global study of religion because it allows us to avoid a Western- or Christian-centric definition of religion. For example, religious service attendance is an important part of being a Christian in many countries. However, other religions, such as Hinduism, Buddhism, and many folk religions, do not emphasize attending services. Instead, holiday celebrations, diet, lifestyle, and other practices are central.

By including multiple dimensions of religiosity in our databases, we improve our ability to identify varying levels of religiosity, even among the non-religious. We also avoid stereotyping “religion” and leave our data open to many different forms of religion, belief, culture, and worship.

Our projections based on this data will provide a more multi-dimensional picture of the religious landscape than those based only on identity.

(3) Agent-based models

Another challenge of traditional methods is basing projections on assumptions about group-level data rather than on the behavior of individuals that respond to societal conditions.

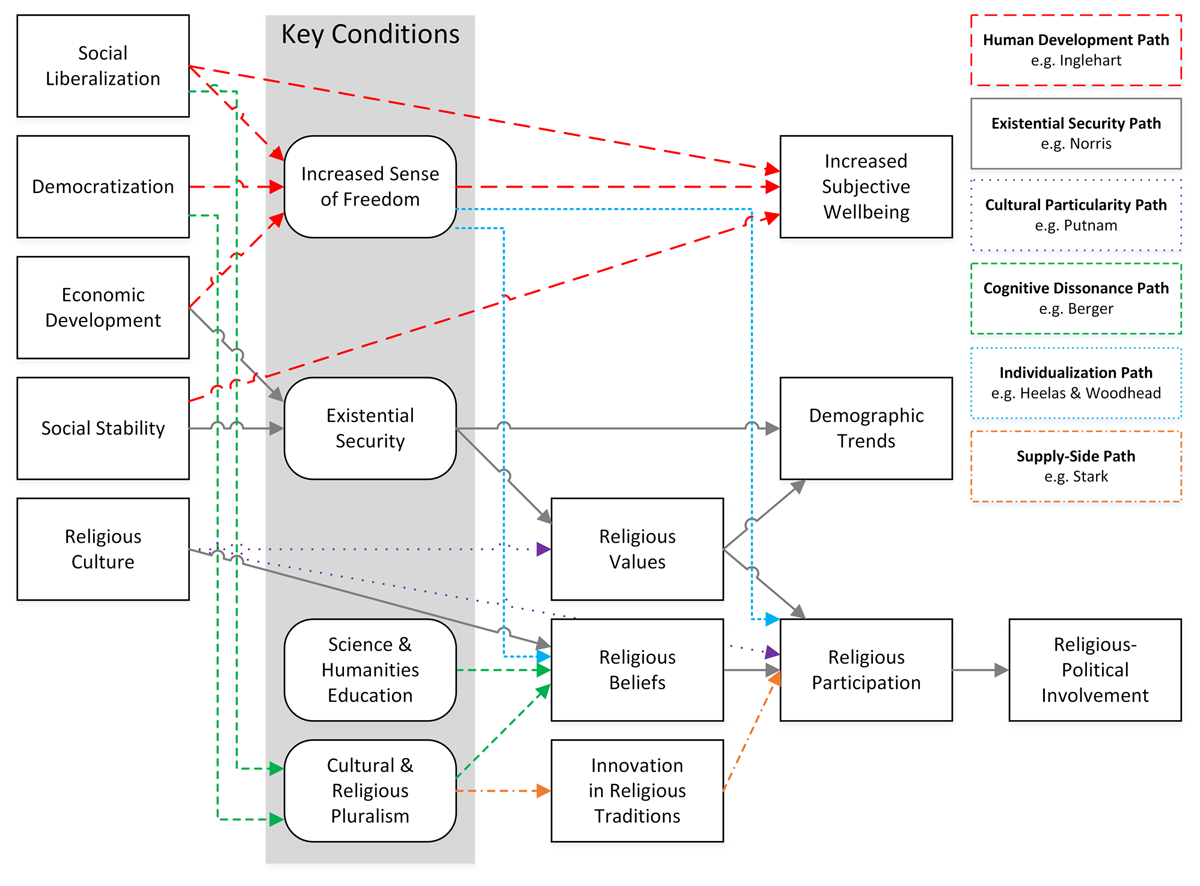

Using agent-based and system-dynamics models allows us to include more nuance in our projections, track how individual behaviors lead to group dynamics, and identify which factors are the most influential in religious change. Our computer models act as artificial societies upon which we can test policies and watch the future unfold under different conditions.

We code these models based on various theories of religious change, setting up equations between factors such as religious pluralism, education, the fertility rate, and religiosity. Then, we test the results against real-world data to validate that our model is accurate to real life.

Rather than applying our calculations to faceless groups, our simulations contain thousands of AI “agents.” We program these agents with select behaviors, goals, and ideas and see how collective behavior emerges from the individual agents.

Whereas traditional demographic methods impose calculations on monolithic groups, we see how group behavior arises from individual behavior.

The real impacts of MRC

We want to advance simulation engineering. Our agent-based models will prove it’s possible to run large artificial societies with complex agents in massive networks of distributed computing machines. We will provide innovative visualizations to help users interpret what’s going on in the artificial societies and the lives of the agents.

We will forge new directions in the demographics of religion. Since our models focus on religious change, they will deliver proof of concept for a new approach to studying (non)religious identity and change. We invite the demographic study of religion to expand beyond its traditional methodological boundaries.

Our models will engage with and challenge theories in the scientific study of religion. When we create our models, we combine multiple theories of religious change into a single interconnected web. This will encourage more interdisciplinary cooperation and demonstrate that agent-based models are sophisticated enough to both test these theories and run according to them.

In our religion models, our agents have unique personalities, get married, have children, and are connected to each other in social networks that influence their stance towards religion.

For example, in “Religious exiting and social networks: computer simulations of religious/secular pluralism,” we investigated the influence of one’s social network (family, co-workers, and (non)religious community) on his/her (non)religious belief. We programmed hundreds of agents who performed thousands of interactions with other agents, each interaction making them more or less in favor of being religious.

And from these micro-level interactions emerged overall group behaviors and trends of religious switching.

In “Post-supernatural cultures: there and back again,” we constructed an entire miniature country with economic, environmental, social, and technological factors which interacted in complex ways to push individual agents toward religion or nonreligion. Overall patterns emerged from the complex choices of individual agents and we were able to trace which environmental or cultural factors had the strongest influence on religious change.

Our agent-based models will be made available to policy-makers, academics, and the general public, providing demographers with a tool to create more accurate demographic projections. This will allow for better civic planning projects.

A more accurate, but imperfect look into the future

Measuring religious change and forecasting the future of religious change are incredibly complicated tasks with a high possibility for error. Civic planners rely on demographic projections, regardless of how (in)accurate they might be. We are tackling multiple problems in this field through our advanced data-gathering techniques and agent-based models. Our work will improve the demographics of religion and system engineering and ultimately produce more accurate projections of religious change.